Main page content

Confronting Our Electronic Tobacco Future

When MeLisa Creamer decided to enter the field of public health, her hope was to make a difference in the health of kids and young adults. She never imagined, however, that her future work would have anything to do with tobacco. It seemed like a health problem that had already been solved, at least from a research perspective.

“I thought, ‘We know that cigarettes are bad and cause cancer, so we understand that we should not smoke them,’” says Dr. Creamer, now an assistant professor of health promotion and behavioral sciences at the The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Public Health.

Creamer also believed, correctly, that there had been dramatic decreases in the numbers of tobacco users over the previous few decades.

It was true that rates of tobacco use had gone way down. But the numbers of people still using tobacco, and the damage that tobacco use was causing, remained staggering.

UT researchers and innovators are addressing the urgent challenges of tobacco use and addiction on many fronts. We are leading the way in addressing tobacco use both on our campuses and within the larger communities of which we're part. We're investigating the psychology of quitting, and developing programs to help. It's an urgent health challenge, and one we're committed to meeting head-on.

“I think that in my mind these successes had solved the issue,” she says, “and there was little to be done and other issues on which to focus.”

Creamer’s interest in tobacco began to shift while working on her Master’s degree at the Austin campus of the UTHealth School of Public Health. Two of her professors, Drs. Cheryl Perry and Melissa Harrell were involved in working on the 2012 Surgeon’s General’s Report “Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults.” They hired her to help with the report, and what she found during the course of the project was a revelation.

It was true that rates of tobacco use had gone way down. But the numbers of people still using tobacco, and the damage that tobacco use was causing, remained staggering. Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in Texas, responsible for the deaths of more than 28,000 Texans every year. Half a million Texas children under the age of 18 are smoking, and many of them will ultimately die of tobacco-related causes.

So it is a public health issue of vital and continuing importance. There is also, she learned, a great deal of important scientific research yet to be done.

“I realized that a lot of stuff was still unknown,” she says. “A lot of diseases—not just lung cancer—are linked to tobacco use. A lot of nuances in the area still need to be figured out. And this was a couple of years before vaping became an issue. Now research in this area is even more important and complicated than when I first started.”

Creamer was hooked. She went on to earn her doctorate in epidemiology, writing her doctoral dissertation on tobacco use and co-varying behaviors. She contributed to the 2014 Surgeon General’s Report on smoking and health. She became coordinator of the administrative and scientific core of the Texas Tobacco Center of Regulatory Science on Youth and Young Adults (TCORS), which is based at the Michael & Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living in Austin. And she was one of the senior scientific editors on the 2016 Surgeon General’s Report “E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults.”

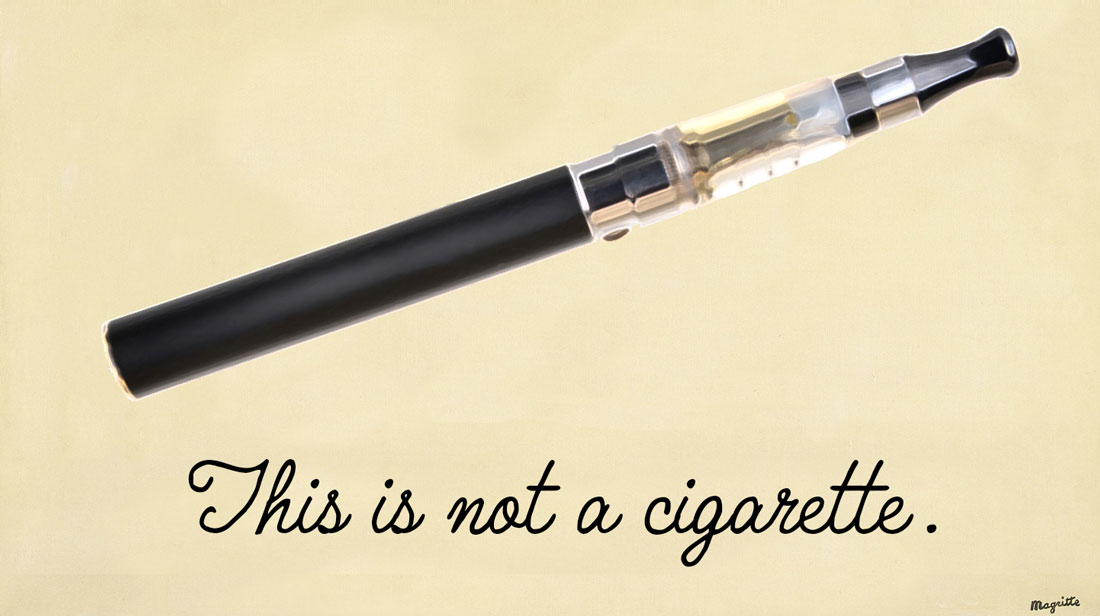

The Rise of Vaping

Much of the work that Creamer has done, since joining Perry, Harrell, and Kelder as faculty with TCORS and at the UTHealth School of Public Health, has focused on the explosion of new and newly popular delivery mechanisms for nicotine, including e-cigarettes, vape pens, and hookahs. She’s interested, in particular, in how the emergence of these new products is affecting tobacco and nicotine use among the young.

“These are traditionally people who haven't used tobacco products,” she says. “They aren’t traditionally smokers and aren’t among those who want to use an e-cigarette to quit smoking. For this group, e-cigarettes are a sort of cool device that has a lot of flavors and they want to go ahead and try it. But what happens to them once they use the product? Do they only use this product, or do they move on to other tobacco products, like cigarettes?”

E-cigarettes first came on to the market in 2007, but didn't become popular until a few years later, at which point their popularity exploded, particularly among young people. A 2015 study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that the number of middle and high school students using electronic cigarettes tripled between 2013 and 2014. In 2015, for the first time, use of e-cigarettes in youth and young adults surpassed use of conventional cigarettes.

It’s only in the past few years, says Creamer, that the public health community has fully recognized what a major public health challenge e-cigarettes and related products represent. That recognition has led to an explosion of research on the subject, but it will be a while before there is the evidence base to truly understand the public health implications of e-cigarettes and to formulate best practices and policies.

“There are so many unknowns about these products,” she says. “For cigarettes we have 50 years of surgeon general's reports that document health effects. In 1964 we had the first report that showed the link between lung cancer and smoking, but now cigarette smoking has been linked to diseases in nearly all major organs, including type 2 diabetes, through 50 years of evidence. We are just starting the process with e-cigarettes.”

These unknowns, says Creamer, include such fundamental questions as whether there is a link between using e-cigarettes and cancer, how much nicotine is delivered through the various devices, whether secondhand vapor is harmful in some of the ways that we now know secondhand smoke is, whether addiction and quitting patterns look different in e-cigarette users, and whether nicotine delivered through e-cigarettes can effect fetal and postnatal development.

We don’t even know, she says, whether e-cigarettes will prove to be a net harm or benefit to the public.

“Within public health there's a division,” she says. “Some people are saying that e-cigarettes are a harm reduction device, that if we can move everyone from combustible tobacco to e-cigarettes then we are going to have decreased mortality rates from cancer and other diseases associated with smoking. But we haven't seen the evidence that we can effectively move people from one product to the other. And a lot depends on the population you are considering. We are close to having nearly 10 studies that show students and young adults who use e-cigarettes have higher odds of transitioning to using conventional cigarettes.”

The purpose of the 2016 Surgeon General’s Report, of which Creamer, Perry, Harrell, and their UTHealth colleague Steven Kelder were editors, was to take stock of the current state of the science of e-cigarettes; to survey the ways e-cigarettes were sold and marketed; and to recommend policies to address both what is known and what is unknown.

“Unlike other Surgeon General's reports,” says Creamer, this report ends with a call to action. It says to the people who are stakeholders—whether it’s health professionals, teachers, parents, policymakers or scientists—that they can and need to have a role in changing what happens with e-cigarettes.”

Building the Evidence Base

In addition to working on the Surgeon General’s Reports, Creamer and her colleagues are doing their own research into tobacco use among youth. Their projects include a study that looks at whether text messages can be an effective medium for communicating health information about tobacco products to youth, and a study of young women and e-cigarette use. Their largest research projects are two longitudinal cohort studies in which youth and young adults are surveyed every six months, over a total of 3 years, and asked about their tobacco use behaviors specifically around cigarette, e cigarette, cigar and hookah use.

...the research has to be done, fast and well, so that the public can make informed decisions about how to handle e-cigarettes and how to make policies that protect and preserve the health of our young people.

“We also ask about other things that may influence their tobacco use,” says Creamer, “so we ask if their parents or friends have used these tobacco products, what they think about them, which products are new and emerging. We ask if they know these are tobacco products, what are their harm perceptions, do they think they are extremely harmful or not that harmful. We ask if they would date someone who used these products.

“They report to us how much advertising they have seen or are exposed to, because marketing and advertising is a huge influencer of whether anyone would use a product. We also collect objective advertising. We go into the point of sale: the convenience stores, the drug stores and places around schools. We go in prior to surveying the students so we get an idea about what they are seeing as well as what they are reporting back to us. For example, where the products are displayed, the types of promotions that are occurring around the products, and that sort of thing.”

Creamer’s years of research on e-cigarettes have led to many individual insights, which contribute to one big insight. The specific ones include:

- Many young people have profound misperceptions about e-cigarettes, including that they don’t contain nicotine, and that the vapor is basically harmless water vapor.

- The flavors in e-cigarettes may contribute to youth, in particular, using them as weight loss or weight management devices.

- Peer influence is important. You’re more likely to smoke e-cigarettes if your friends are.

- In youth, at least, e-cigarettes seem to be a gateway to conventional cigarettes.

The big conclusion is that it’s an incredibly fast-changing environment in which the science and its health implications aren’t yet clear. That means that the research has to be done, fast and well, so that the public can make informed decisions about how to handle e-cigarettes and how to make policies that protect and preserve the health of our young people.

“I think that's where our biggest impact lies,” says Creamer. “It’s in publishing and providing evidence. We have close to 30 papers that have been published or are in press across our three projects. Every year we have had pilot funding and so we have smaller projects that have focused on the priority areas of the FDA. With each of these, we have been able to spread the word within the scientific community and have built a scientific base because we understand that at the FDA level they are not going to be able to provide more regulation without good justification.”

News Contact Information

Jenny LaCoste-Caputo: jcaputo@utsystem.edu • 512-499-4361(direct) • 512-574-5777 (cell)

Karen Adler: kadler@utsystem.edu • 512-499-4360 (direct) • 210-912-8055 (cell)

Melanie Thompson: mthompson@utsystem.edu • 512-499-4487 (direct) • 832-724-1024 (cell)