Main page content

Precision Medicine and the Future of Mental Health

Throughout The University of Texas System, psychiatrists and psychiatric researchers are working to move the field of mental health into the 21st century and beyond. They're zeroing in on which treatments work for which patients, diagnosing earlier and with more precision, and working to reform the mental health systems that struggle to meet increasing and overwhelming demand.

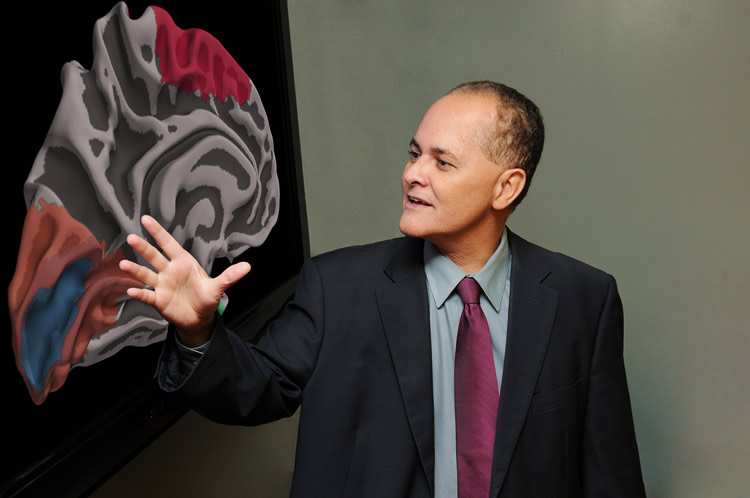

Not too long ago, psychiatrist Jair Soares and his colleagues at UT Health Science Center at Houston decided to see if they could teach a computer to diagnose bipolar disorder from brain scans of kids.

It wasn’t as science fictional a prospect as it sounds. Artificial intelligence software has gotten quite good, over the past decade or two, at reading visual data and selecting out unique or recurring patterns. It’s why the NSA can pick Matt Damon out of a crowd of people in a closed circuit video feed. It’s why Google Images shows you a bunch of cars when you type “car” into its image search window, even when those images don’t have any textual metadata that says “car” or “Chevrolet.”

We also know some things, from advances in neuroscientific research, about how conditions like depression and bipolar disorder affect the brain. We know some of the regions of the brain that usually get smaller or bigger when people are suffering from these disorders. We know some of the neural circuits, particularly those related to emotion regulation and reward processing, where the connections grow thicker or attenuate.

Our understanding is far from perfect. The brain is an incredibly complex organ, and the technologies to analyze it are still in their infancy, or at best their adolescence. But things are far enough along that Soares thought it was worth the effort. So he and his team took functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans of kids diagnosed with bipolar disorder, gave their machine learning software some basic diagnostic assumptions about what to look for, and then trained the software.

They went back and forth with the algorithm, scoring and correcting each round of its predictions. As the iterations proceeded the software got better and better at differentiating a scan of a child with bipolar disorder and a scan of one without. When the software was as good as it could get, based on the original set of scans, Soares and his team gave it 32 scans it had never seen before. 16 of them were of kids with BPD, and 16 were healthy controls.

It picked right in 25 out of the 32 scans, for a diagnostic accuracy rate of 78.1%.

“That’s pretty good,” said Dr. Soares, who is director of the UT Center of Excellence on Mood Disorders, “but it’s not necessarily better than what a psychiatrist can diagnose without an fMRI, and it’s much, much more expensive. So there’s a cost-benefit analysis that doesn’t push us, yet, in the direction of using these tools clinically. The hope, however, is that as we continue to refine these tools and analyses, and as we combine them with other types of tests and biomarkers—genetic biomarkers, for instance—we will be able to create a neurobiological profile that offers much higher specificity.”

The future Soares is describing is one in which “precision medicine”—the capacity to really tailor treatments to specific populations and individuals—applies not just to conditions and disorders like cancer, diabetes, and heart disease, but to mental health conditions as well.

It’s a future in which those of us with a mental health condition, or who are at high risk for developing one, don’t just tell our doctor or social worker or therapist what we’re subjectively experiencing. We get brain scans, genetic analyses, electroencephalograms, and other diagnostic tests. Then we integrate those results with the more qualitative, experiential information that comes from talking to a well-trained clinician. Then we strategically, scientifically and with much greater precision anticipate, treat, and in some cases even pre-empt a mental health disorder.

This future won’t be perfect. The human body is too complex a network of interconnected systems for perfection. Chemotherapy doesn’t work for all cancers and patients. Statins don’t reduce cholesterol levels for everyone to the same degree. Ibuprofen is better for some people and pains; acetaminophen works for others.

There’s too much going on in our brains to allow for perfectly tailored treatments. Yet the precision with which we diagnose, treat, and protect against mental illness could be vastly improved.

“I compare it to the field of oncology, where there has been a major transformation over the last few decades,” said Soares. “Now we can not only diagnose specific types of cancer, we can often go even further and identify sub-types of that cancer, and then also the treatments that will be most efficacious. We are at least a decade or two away from really understanding how these mental disorders come about, and from diagnosing them in a truly scientific fashion. But when we can do that, with mental disorders, that’s what will truly transform the work. Early diagnosis, in particular, will be transformative.”

Soares and his collaborators at UT Health are among an extraordinary assembly of researchers, across the UT System, who are helping to bring this future into being. Their stories have a lot to tell us about what mental illness, and health, will look like over the next few decades.

Take 20 Laps around the Track and Call Me in the Morning

One of the more fascinating aspects of this precision future, for UT Southwestern psychiatrist Madhukar Trivedi, is that we may discover that many of the most effective drugs, therapies, and treatment technologies for serious mental health conditions are already here. They just need to be applied with more precision.

An enormous amount of progress, for instance, is likely to come from psycho-pharmaceuticals we already have, like SSRIs for depression, that are prescribed with greater sensitivity to an individual’s unique physiology. We may discover that existing drugs that were developed for other conditions, like anti-TNF drugs for arthritis, are effective in treating depression. The most precise recommendation for treatment, for an individual patient, could be a combination of existing antidepressants with good psychotherapy.

We may even discover that the best treatment, for some people, is something as simple, inexpensive, and universally available as exercise.

“There isn’t a drug company that is selling exercise, but in a sense it is a novel mechanism,” said Trivedi, who is Director of the Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care in the Department of Psychiatry at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “It has all sorts of effects that we believe can be efficacious with depression, including neurogenesis and anti-inflammatory effects.”

The fundamental challenge, both in developing new treatments and in refining and repurposing existing ones, is the same. It’s understanding this thing—these conditions, these experiences, these disruptions in the normal course of psychological functioning—we call mental illness.

Trivedi’s particular white whale, in the ocean of mental illness, is depression, which affects as many as one in eight Americans over the course of a lifetime.

He served as one of the Principal Investigators of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, which at the time was the largest and longest study on the treatment of major depressive disorder and is considered a benchmark in the field of depression research. Over seven years, it followed thousands of people as they treated their depression with various anti-depressants to see if patterns emerged about what worked, or didn’t work, for what kind of person.

Currently, he is lead principal investigator of the national, multi-institutional team conducting the “Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care (EMBARC)” project. The goal of the EMBARC project is to go much deeper, with fewer people, to really begin to understand how depression plays out in the brain, and how the depressed brain changes over time in response to various treatments or lack of treatment.

The overall picture of depression that has coalesced for Trivedi, over the course of his decades of research, is of an incredibly complicated brain dysfunction that may be more usefully understood, and therefore treated, as a constellation of different sub-types of depression.

Already, for instance, there is evidence that a significant minority of cases of depression, maybe 15-20 percent, are caused or influenced by inflammation in the brain. People with inflammation-related depression may benefit more from treatments that focus on reducing the inflammation, like arthritis drugs, than from traditional anti-depressants, which affect the reward processing and emotion regulation circuits in the brain.

“What we have right now are some very good signals, from the research, about more precise matching of patients to treatments, but it’s not clinical yet.”

Some other types of depression, or depressed patients, may benefit from the ketamine group of drugs, which act on a different receptor in the brain than SSRIs do.

“There is another, smaller groups of patients in whom we see changes in an area of the brain called the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex,” says Trivedi. “There is some evidence that the type of depression that corresponds to that responds well to a treatment called Transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS. It involves putting a magnet outside of the skull and giving what are basically magnetic pulses, at low amplitudes, to certain parts of the circuit. It changes the circuit itself, and that affects the behavior and emotion.”

Trivedi’s hope is that as our picture of depression(s) becomes clearer, what will evolve isn’t so much a science fictional future as one in which mental health care workers have diagnostic tests and treatment algorithms that are as powerful and predictive as what clinicians in other disciplines already have.

That could mean simple blood tests, for instance, that help identify people with early signs of mental illness. Then people who are flagged in that initial screen would get more powerful and precise tests. At that point clinicians would take all that information, along with our medical histories and other relevant data, and recommend the treatment that’s most likely to work for our unique biological profile.

The prescription might be for an SSRI, or a combination of SSRIs. It might be for ketamine, or anti-inflammation drugs. It might be for some form of neuro-modulation, like TMS. It might be for a new drug or procedure that hasn’t been developed yet. Or it could be for exercise, a better diet, and more sleep.

“This is just the beginning,” says Trivedi. “Our main goal at the Center is to get to a point where we will develop these tests that will enable precision. But we are not there yet. They conducted the Framingham Heart Study 65 years ago. We have not done the same thing for depression. What we have right now are some very good signals, from the research, about more precise matching of patients to treatments, but it’s not clinical yet.”

A Different Kind of Precision

For Steve Strakowski, the new chair of psychiatry at the Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin, precision mental health means two very different kinds of things.

As a researcher, he studies how neuroimaging technologies can help us better understand bipolar disorder. In this role, he seeks greater precision in diagnosing and treating people, and an ever more precise understanding of how bipolar disorder and other mental health conditions affect and are affected by the brain. His team is trying to understand how the conditions starts in adolescents in the first place and whether is it possible to prevent its development, or at least prevent its progression to a life-long recurrent illness.

As a player in efforts to restructure mental health services in central Texas, the challenge is very different. He’s looking to help transform the mental health systems that serve people when they are in crisis (or before they are in crisis, when possible).

In this context, precision is less about new drugs and improved brain scanning technologies than about better designed facilities, more integrated bureaucracies, and targeted policies that enable different types of mental health care workers to serve patients in the most effective and efficient ways.

“The field is at a point where if we could just improve access and care delivery that would go a long, long ways toward improving mental health,” says Strakowski. “Because right now less than half of the people who need care get effective treatment. That is the low bar, just to get people access to the treatments we already know are effective, but it would make an enormous difference.”

At the center of Strakowski’s vision for better mental health in Austin, and ultimately in Texas, is a more coherent and refined continuum of care designed to meet people where they are.

Such a system of care would include, among other things, more uniform systems and standards for diagnosis and referral, so that not just doctors and nurses, but school counselors, social workers, police officers, sheriffs and others throughout the overlapping systems that deal with mental health would be better equipped to get people into the right kind of care.

It would expand and reimagine the kinds of spaces where people could go for help, with more types of inpatient care, more levels of outpatient care, and more transitional services and sites for people coming into and leaving the system.

An improved system would also better coordinate the expectations and responsibilities of different kinds of mental health care professionals, so that everyone was providing the care and making the decisions most suited to their training and expertise.

“Having someone with a typical case of depression see me, for example, at an elevated cost relative to other potential providers, is a poor use of resources,” says Strakowski. “What makes much more sense is working as a team, providing a continuum of care through providers in much the same way that we would like to provide a continuum of facilities. That means leveraging and integrating psychiatric social workers, psychologists, primary care providers and counselors more effectively than we do now.

“Right now less than half of the people who need care get effective treatment. That is the low bar, just to get people access to the treatments we already know are effective, but it would make an enormous difference.”

“It means relying on pharmacists to do a lot of med assessments and monitoring, and having them advise primary care physicians and psychiatric nurse practitioners. Then you bump it up to the psychiatrist when you need a psychiatrist, to do a medical assessment and provide complex patient care planning, but you don't have physicians doing the work of therapists and counselors and pharmacists (and the converse, of course). Frankly, the latter folks are better at their jobs then physicians anyways!”

At the heart of Strakowski’s vision is a long-term partnership between Dell Medical School and the big mental health stakeholders in the region, including the Department of State Health Services, Austin Integral Care, facilities like Austin State Hospital (ASH), private and non-profit health care systems, philanthropic organizations, the criminal justice system, and community organizations and activists.

In one particularly promising version of this collaboration, Austin State Hospital would become a comprehensive ecology of care, with a diversity of settings, services, and clinicians on site to meet the needs of patients at every step of their care and recovery. It would also serve as an applied laboratory where researchers and clinicians would collaborate to evaluate what treatment models were proving effective, improve or discard those that were less effective, and then export the best models to the rest of the state and out into the communities.

One of Strakowski’s inspirations for this kind of integrated, multi-tiered system, ironically, is early 19th century Wisconsin. Back in the 1800s, he explains, the state designed and implemented a really exceptional continuum of care for people with mental health issues. It worked fabulously, both in terms of better outcomes for patients and lower costs for the state. It was shut down, however, because it didn’t align with the broader 19th century notions of how mental illness should be handled.

“It went against the dogma of the era regarding how we should treat people with mental illness, which was to put them in the big hospitals, often for extended periods of time,” he says. “In our redesign, we want to emphasize outcomes not ideology.”

The good news, says Strakowski, is that the 21st century is finally coming around to seeing the wisdom of 19th century Wisconsinites. Austin, in particular, seems ready to try something new (or old).

“I am excited to be in Austin,” he says. “I came here to do something big and make a difference. I could have stayed at my old job; it was a great job. But I wanted to try to do something new, and I have been really pleased with Austin's response to this. The leaders in the city have been nothing but supportive and progressive, in thinking about mental health. So I'm cautiously optimistic that we are going to make a difference. We probably won’t end up where we think we will, but we are going to end up somewhere really good and do something meaningful.”

The Holy Grail of Early Detection and Intervention

Perhaps the greatest promise of precision mental health lies in its potential for diagnosing problems early and giving people, particularly young people, the tools and treatments to recover sooner and better, or even to avoid developing the disorder in the first place.

Soares and his colleagues at UT Health, for instance, are working with a group of about 200 adolescents in Houston with bipolar disorder. They’re giving them regular fMRI scans and genetic analyses, and doing scans and genetic analyses of their siblings and parents as well. They’re also tracking the treatment the participants are receiving.

“The broad hope,” says Soares, “is to identify biomarkers that will help us understand the risk, and then we can link those biomarkers to attempts to intervene early. And as we know more about which interventions work best with which disorders and individuals, the treatments will improve as well. I believe this could be a very powerful way to prevent this disease from taking hold or from progressing to the point where patients are left with lasting impairment.”

In the Dallas area, Trivedi and his colleagues at UT Southwestern are reaching out to young people before they’ve even developed a disorder, selecting for those who have mental illness in the family.

“We connect with every incoming freshman, at 15 high schools, and ask them if their parents have depression or bipolar disorder,” says Trivedi. “What we’re going to be able to do, with that information, is identify people who are at risk, primarily because of a family history, and then follow them for 10 years, doing a full EMBARC type analysis three four times a year.”

The tragic certainty, says Trivedi, is that some of these kids will develop bipolar disorder or depression during that time. That would be the case, statistically, even in a group that didn’t have mental illness in the family. By following this cohort closely, however, they can offer more immediate and better help to those who do begin to suffer. And by conducting deep and ongoing analyses of their genes, brains, environments, and the development or lack of development of mental illness, they will understand ever more about how mental illness develops in the brain. That, in turn, should lead to better interventions, and more prevention, in the future.

“Right now we don’t have a very well defined package of what needs to be done,” says Trivedi. “We have some indications, though. Managing and reducing stress, improving responses to bullying, improving interpersonal skills, increasing mindfulness, avoiding drug and alcohol use—there are good indications that these lower the risk of developing depression. There are some very promising indicators, but we need to know more. That’s why we’re doing the studies.”

For Strakowski, the questions are as much about how to get people into the right treatment setting as quickly as possible as they are about advances in diagnosis and treatment.

He gives the hypothetical example of a 20-year-old who lives in a rural area of Texas who is experiencing his first manic episode. Right now, too often, that 20-year-old would end up being sent to a place like Austin State Hospital, hours away from his family, because the local mental health facilities aren’t prepared to deal with his situation. That might be “the least bad option,” Strakowski says, but it’s not a good one.

“If your kid had pneumonia, would you be satisfied to have your kid sent three hours away for his pneumonia care? Is that good care? What it should look like is that this kid starts with two days at a regular general hospital with some tele-psychiatry support, perhaps from Austin. Then he can move for a period of time to a community mental health center, with some additional support from a central organization, and so on. The goal is to use this hub we want to create as a model for the continuum and then push as much of the continuum out to the communities that would provide better care, less expensive, closer to home.”

This will require a profound transformation, says Strakowski, of the way that mental health care systems are developed, funded, integrated and managed. It won’t be an easy or quick transformation, but it will happen. And we’ll all benefit as a result.

“We look back at treatment 100 years ago, and say, ‘Those people were barbarians.’ I am reasonably confident that 100 years from now, that is how people will see us. In both cases, people leading care were and are doing the best they can within the limits of the structure and knowledge. We’ll get better, and understand more, over time, but it’s a long process.”